Shirley Jackson - The Lottery

Question Authority before Authority Questions You

Another old homework of mine.

Course: The American Short Story of the 20th and 21th century

Student: Sabine Stebel

Fachsemester: 2

Semester: Summer term 2015

Type of course: Hauptseminar

Lecturer: Prof. Dr. Sieglinde Lemke

Table of content

2 Fertility and social control through human sacrifice

2.1 Prevention of mutiny against the patriarchal system

2.1.1 Patriarchal organization of the village

2.1.2 Controlled violence as a social vent

2.2.1 Mob behavior, obedience and diffusion of responsibility

3 The effect of the writing style on the reader

1 Introduction

Before WWII, as early as 1933, the US press covered Nazi violence against Jews in Germany although not very prominently. It also covered the Nuremberg Laws 1935 and 1938-1939 it reported on Germany’s anti-Semitic legislation (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum). But the most common discourse on the Holocaust in the United States, then and now, told the story of “the culpable, sometimes willed obliviousness of American gentiles to the murder of European Jews; […] which made the United States a passive accomplice in the crime” (Novick 19), (Florida Center for Instructional Technology, “Holocaust Timeline: Aftermath”). The US and his citizens were classical, indifferent bystanders. Even after WWII they did not want to admit, that the inmates of the liberated camps were Jews who had survived the Final Solution (Novick 65).

“In the spring of 1945 […] at breakfast tables across America, the Holocaust sprang from the newspaper page” (Novick 63). But “indeed, everything about the contemporary presentation […] was congruent with the wartime framing of Nazi atrocities as having been directed, in the main, at political opponents of the Third Reich” (Novick 4). “General Eisenhower described the sites as “German camps in which they have placed political prisoners” (Novick 64). The Saturday Evening Post described the Holocaust at that point as “extermination for people who had dared to oppose the Nazi regime […] had been members of the resistance [or] had the misfortune to be born Jews” (Novick 65).

This was the historical, political and social climate in which Shiley Jackson published her short story The Lottery in June 1948. The post war time was a time in which the Americans too had to face the fact that they also had been bystanders, just like the Germans. Especially the American Jewry had to face the gruesome truth that “The Final Solution may have been unstoppable by American Jewry, but it should have been unbearable for them. And it wasn’t” (c.f. Novick 30). In The Lottery “despite assurances during the late 1940s that “it couldn’t happen here,” a microcosmal holocaust occurs in this story and, by extension, may happen anyplace in contemporary America” (Yarmove).

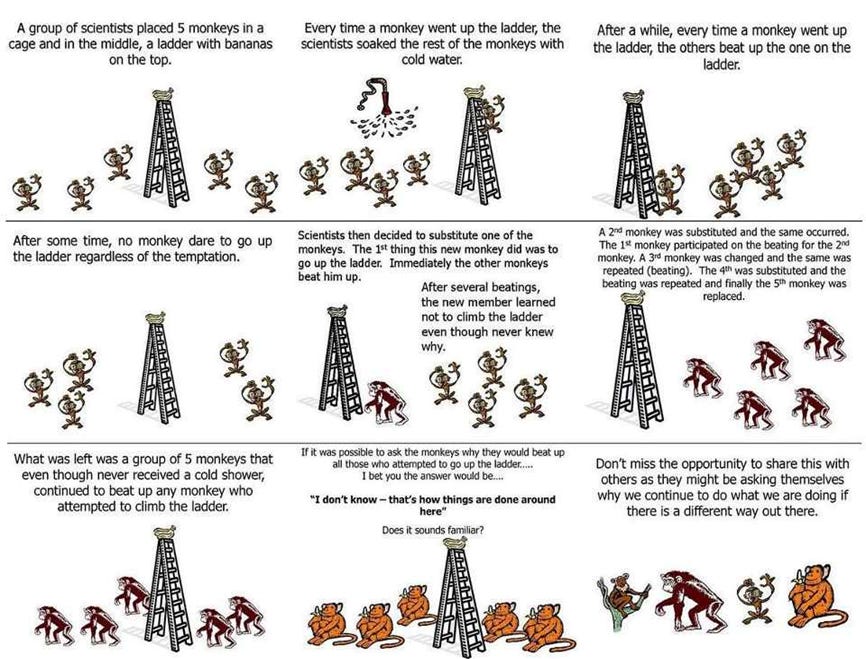

This question as to why people accept rules set by authorities without rebelling against obvious unfairness und why “traditions” or “traditional” hate against the Jewish people persist over centuries without being questioned, shaped the psychological and behavioral sciences up to the mid 1960 which resulted in two famous experiments. In 1967 Stephenson showed how traditions are transmitted, although the source of this tradition is already unknown, in an Experiment that inspired the famous management and internet fable called The 5 Monkeys Experiment. This experiment was preceded by Milgram’s two papers: Behavioral Study of Obedience (1963) and Group pressure and action against a person (1964) which tackled the question of obedience to authority in human societies. Milgram directly states in the introduction to his paper Behavioral Study of Obedience that he wanted to investigate and try to understand the mechanics of Obedience underlying the Holocaust.

It has been reliably established that from 1933-1945 millions of innocent persons were systematically slaughtered on command. […] These inhumane policies may have originated in the mind of a single person, but they could only be carried out on a massive scale id a very large number of persons obeyed orders. Obedience is the psychological mechanism that links individual action to political purpose. It is the dispositional cement that binds men to systems of authority. (Milgram, “Behavioral Study of Obedience”)

Shirley Jackson addresses in her short story the main questions of the post WWII period in the US: Mans cruel, atavistic nature only disguised by a thin layer of civilization, “scapegoating, ritual cleansing, gender, class structure, arbitrary condemnation, and sanctioned violence” (Shields).

2 Fertility and social control through human sacrifice

One of the main, and most obvious, concerns the short story addresses is the topic of tradition in human behavior and society, in this case the tradition of a yearly human sacrifice. On closer inspection though, this very obvious main topic becomes surprisingly complex in its social ramifications.

Although “the original paraphernalia for the lottery had been lost long ago” and “so much of the ritual had been forgotten or discarded” (Jackson 588), the villager still follow this traditional ritual of the yearly lottery. The villagers have altered some minor details like the replacement of wooden chips with slips of paper but they completely discarded the religious aspects the lottery once had. “There had been a recital […], performed by the official of the lottery” and a “ritual salute, which the official of the lottery had to use” and some people “believed” that the official either “used to stand just so” or “was supposed to walk among the people” (Jackson 588). The use of “believe” two times over in one sentence strongly indicates as to possible former religious roots of this lottery ritual. This assumption is further supported by Old Man Warners’s comment that once, perhaps in his youth, when older people still remembered more of the roots of the ritual, there was the saying that “Lottery in June, corn be heavy soon” (Jackson 588).

As a good harvest has always been essential to the survival of human cultures, it is feasible to assume, that the lottery’s roots may have once been grounded in an old fertility ritual or in a ritual to appease a god or gods as they can be found in many cultures in ancient history. The date also points as to this possibility. The 27th of June is halfway in between the summer solstice (June 21) and the Independence day on June 4. Midsummer’s day has a long heathen tradition of fertility rituals while the American Independence Day stands for democracy, freedom and justice (Shields). By placing the day of the lottery exactly in between these two dates the dual use of this lottery is again emphasized as on the one hand grounded in religious fertility rituals and a means of securing state or social control over the population.

“Lenemaja Friedman has compared the stoning of Tessie Hutchinson to the festival of the Thargelia in ancient Athens” (c.f. Gibson). The Carthaginians sacrificed little children (“Old History Is New Again: Ancient Carthaginians Did Sacrifice Their Children”) as already Diodorus describes:

“They also alleged that Cronus had turned against them inasmuch as in former times they had been accustomed to sacrifice to this god the noblest of their sons, but more recently, secretly buying and nurturing children, they had sent these to the sacrifice;[…]” (Diodorus 20.14.4) (Siculus).

The ancient Jews sacrificed children to a god named Moloch or Molech: “Do not give any of your children to be sacrificed to Molech, for you must not profane the name of your God” (Leviticus 18:21). The Celts also sacrificed humans according to Strabo

“It is said they have other modes of sacrificing their human victims; that they pierce some of them with arrows, and crucify others in their temples; and that they prepare a colossus of hay and wood, into which they put cattle, beasts of all kinds, and men, and then set fire to it” Geography (6.4.5) (Strabo).

As the religious background of the lottery ritual seems to be all but forgotten, it has turned into a roman like decimation which was a human sacrifice used in the roman army to discipline troupes and to assure obedience and by this to prevent mutiny or desertion. The most famous incident, after which the decimation was carried out, was during the Third Servile War against Spartacus:

“Five hundred of them, moreover, who had shown the greatest cowardice and been first to fly, he divided into fifty decades, and put to death one from each decade, on whom the lot fell, thus reviving, after the lapse of many years, an ancient mode of punishing the soldiers” (Plut.Crass.10.2f) (Crane).

The Roman Author Livius describes this procedure in (ii. 59.9ff)

“When at last the soldiers had been collected from their scattered flight, the consul, who had followed his men in a vain attempt to call them back, pitched his camp on friendly soil. […] he caused the unarmed soldiers and the standard-bearers who had lost their standards, and in addition to these the centurions and the recipients […] who had quitted their ranks, to be scourged with rods and beheaded; of the remaining number every tenth man was selected by lot for punishment” (Crane).

The question thus arises, who are the ones that are to be prevented to mutiny or desert in this village and how is it possible, that this ritual is carried out without any mayor resistance by the village’s population and why is this ritual still carried out without knowing the reasons for its existence?

2.1 Prevention of mutiny against the patriarchal system

Every year one person is killed during the ritual stoning. The process how this person is chosen is interesting from a mathematical point of view. As Richard Williams already pointed out in 1979, this lottery is a two stage process that is not fair. From the mathematical point of view “all of us took the same chance” (Jackson 591) is a blatant lie.

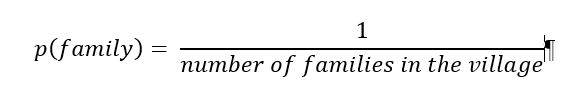

In this two stage process the combinatorial rule of product applies, as an action b (choosing of individual family members) occurs depended on an action a (choosing of the family). This means the probability (p) for a family to be chosen

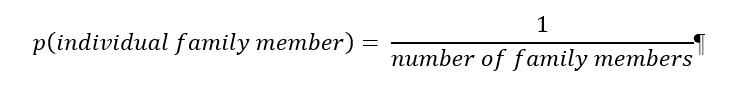

has to be multiplied with the individual probability of the family members which is given by

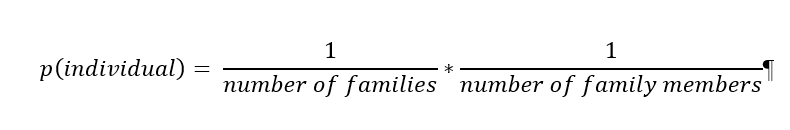

The probability for an individual to be the victim is thus dependent on the size of the family

The bigger the family the lower the second mathematical term and thus the indivudual’s probability to be chosen as the victim of the stoning. (Williams)

It is thus only mathematically logical, that to lower one’s own probability to be chosen in the lottery, a family has to have as many members as possible. This means for the female inhabitants of the village that they have to give birth to as many children as possible, to lower their own probability to be stoned to death in the next year. As “daughters drew with their husband’s families” (Jackson 591) it is also in the interest of the women to give birth to as many male children as possible, to further enhance the size of the family by the addition of daughters-in-laws. This means furthermore that mothers have to encourage their sons to marry as young as possible and to become fathers as soon as possible to further reduce the individual’s probability of being stoned to death by increasing the number of family members by as many male grand-children as possible.

This calculation makes clear, that this ritual serves a threefold purpose. First of all, it secured and still secures the growth of the village population, which is in accord with the possible ancient religious roots based on a fertility ritual. Secondly it secures the female submission to a hierarchical patriarchal system (Oehlschlaeger) as it might be that it is only possible to become a mother in wedlock and no woman wants to draw with a small family and will try to marry into a proliferating family with many male members. Thirdly it secures the social cohesion based on a crime committed as a group which forges a strong communal bond and identity based on a collective guilt and at the same time giving a controlled vent to bottled up aggression.

2.1.1 Patriarchal organization of the village

There a many indications in the text as to the patriarchal organization of this village. First of all those dignitaries conducting the lottery are all male. Mr. Summers the owner of the coal business, Mr. Graves the postmaster (Jackson 587) organize and conduct the lottery and sometimes Mr. Martin the grocer takes care of the black box between lotteries (Jackson 588). This means, that the most wealthy men of the town control the business and the lottery (Shields 415), which is an oligarchic system but not a democracy. This is something that is nowadays euphemistically called post-democracy and perfectly describes what the US has become. The place where the lottery is conducted also emphasizes the power of these dignitaries as the lottery takes place “in the square, between the post office and the bank” (Jackson 587), “the institutions from which Summers, Graves and Martin derive their power”. The people conducting and controlling the lottery “represent authority, power, tradition and conformity” (Shields 416).

The male head of the family it the one to draw the lot in the first round (Jackson 590) and women who have to draw for their men, as their sons are not old enough to take this responsibility upon them, are pitied “Wife draws for her husband, […] (d)on’t you have a grown boy to do it for you, Janey?” (Jackson 589) while boys drawing for their mothers are lauded “Glad to see your mother’s got a mon to do it” (Jackson 589).

Even the children do not respect their mothers. Although the women call their children “the children came reluctantly, having to be called four or five times.” Only when the fathers call do they comply, but then the boys additionally chose to stand with the male members of the family “(h)is father spoke up sharply, and Bobby came quickly and took his place between his father and his oldest brother” (Jackson 589). The women also come “shortly after their menfolk” to the gathering and “join their husbands” while “(t)he girls stood aside, talking among themselves, looking over their shoulders at the boys, […]” (Jackson 587).

Daughter are counted among the family of their husband and “(d)aughters drew with their husbands’ families,[…] (Jackson 591).

When it comes to the Hutchinson family to draw which of them has to die, Mr. Summers only asks Bill if he is ready (Jackson 592), not the whole family, and Bill Hutchinson afterwards “forces the slip of paper out of her (Tessies) hand” (Jackson 592f).

It is only logical, that in a patriarchal system a ritual that helps to secure this social order in favor of the male inhabitants is only resisted by women. Mrs. Adams mentions that “Some places have already quit lotteries” (Jackson 590) and it seems that she is not taking part in the stoning ritual. Tessie Hutchinson, whose name reminds the reader of Thomas Hardies famous novel Tess of the d'Urbervilles and the Puritan spiritual leader Anne Hutchinson (Yarmove) only speaks up when the lot has fallen on her family. Although she is a female victim of society like her famous namesake Tess, she does not fight back until it is too late. Her outcry that “It isn’t fair” (Jackson 593) thus does not seem like a real rebellion against the system but like a “peevish last complaint of a hypocrite who has been hoisted by her own petard” (Yarmove). Michael Callaghan rightfully asks “Is something unfair only when it happens to me, but not when it happens to you? […] That’s usually the way we read the newspapers, […]” (96). But it has to be credited, that Tessie at least “challenges the sanctity” of the lottery by showing up late (Shields 416) and the other women challenge the sanctity by showing up in “faded house dresses” (Jackson 587).

There is furthermore an additional aspect of patriarchal power that has to be taken into consideration. The lottery could easily be rigged to get rid of unwanted persons. While Mr. Adams, little Dave and Nancy take out a folded papers (Jackson 590, 592) both Mr. Summers and Mr. Grave “select a slip” of paper form the box. Tessie in contrast “snatches a paper” (Jackson 592).

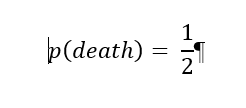

Cards are known to be sometimes rigged in games of cards. Why should these lottery lots not also be rigged? The two dignitaries would be utterly stupid if they did not mark the deadly paper in an inconspicuous way like a slightly different folding angle, a nipped corner or a slight smudge. Some marking that would only be obvious if it was really searched for. If a husband wanted to get rid of his wife, there would be possibilities to arrange this. Of course, Mr. Summers might get rid of his scolding wife this way, but with a 50:50 chance, as the couple is childless, this might be a too high risk to take as in the second round the male head of the family draws last and a rigged card would be no help in a situation with

if the unwanted, scolding wife by chance choses the unmarked lot.

2.1.2 Controlled violence as a social vent

It seems that the yearly recurring ritual of the lottery is not seen as something evil or inherently wrong by the inhabitants of the village. From the behavior of at least some of the villagers it seems that they are anxious and exhilarated for this lottery to be held, especially the boys, in whose future favor this ritual works. “Bobby Martin hat already stuffed his pockets full of stones, and the other boys soon followed his example, […]”(Jackson 587).

Die Dressur zum Gehorsam in der frühen Kindheit und die ein Leben lang wirksame „Identifikation mit dem Aggressor“ verhindern die Entwicklung der Fähigkeit zu Mitgefühl und Solidarität– mit uns und anderen“ (Eisenberg).

This citation perfectly describes the way the children are socialized to accept this brutal ritual of the lottery. This is described at the end of the story as “(t)he children had stones already, and someone gave little Davy Hutchinson a few pebbles” (Jackson 593) to stone his own mother to death. Even the little ones, not really understanding what they are doing, are trained to obedience and to kill without mercy from early childhood on and thus identify as survivors and executors with the aggressive patriarchal society and its ritual of the lottery. They will talk about this ritual, they will perhaps sometime also say as proud as Old Man Warner “Seventy-seventh year I been in the lottery” (Jackson 591) and thus being a murderer of about 76 innocent people.

Informal conversations about events and experiences tend to take the form of "accounts "—naturally occurring conversations in which people attempt to make sense of an experience […]. As such accounts are shared, a social group builds a model of common experience in which the personal experience becomes universal and members of the group see each other and their social world in similar ways. […] In many cases, the account works to justify further or increased violence. (Blume)

The children are actively taught to become bystanders in a microcosmal holocaust. They are taught to be indifferent to suffering and not to feel empathy for the victims. They are taught be become bystanders.

Indifference is not so much a gesture of looking away--of choosing to be passive--as it is an active disinclination to feel. Indifference shuts down the humane, and does it deliberately, with all the strength deliberateness demands. Indifference is as determined--and as forcefully muscular--as any blow (Florida Center for Instructional Technology, “Bystanders”).

“[Der Mensch] verschließt sein Herz gegen Mitleid und andere weiche Regungen und macht sich zum Anwalt seiner Zerstörung. Der Konformismus, der sich auf der Basis einer „Identifikation mit dem Aggressor“ entwickelt, ist mit Feindseligkeit und Bösartigkeit kontaminiert. (Eisenberg)

Of course, the young adults who begin to understand that they also might be the victim of the ritual are nervous like Jack Watson “He blinked his eyes nervously and ducked his head” (Jackson 589) but the older and more accustomed to the ritual the people become, the lighter they take the possible consequences. They still “grinned at one another humorlessly and nervously” or even take the lottery good humoredly like Tessie. And in the end, all is business as usual when Mr. Summers calls to do what has to be done “All right, folks […]. Let’s finish quickly” (Jackson 593). What stories of so many stoning rituals to tell in the evenings, when it is cold and dark outside.

2.2 Black Box Ideology

How is it possible that this “microcosmal holocaust occurs in this story” (Yarmove)?

The ideological mechanism by which the lottery operates is described by the technical term “black box”. In science and engineering a black box is a device, system or object which is mainly seen in terms of its inputs and outputs. The workings of this black box are unknown, not understandable, not of interest or not accessible to the user who does not need this information to operate the system. In NMR spectroscopy the device transforming the input signal via Fourier-Transformation into an NMR spectrum is referred to as black box and scientists working with NMR spectrophotometry normally have no idea what a Fourier-Transformation is or how it works and often do not even know that something like this is needed to generate an NMR spectrum. The term “black box” was introduced during World War II.

The black box originally referred to a top-secret device on World War II Flying Fortresses -- a gun sight with hidden components that automatically corrected for such factors as velocity and wind speed, and provided a relatively untrained gunner with deadly accuracy. The phrase later came to mean any kind of complex equipment not normally maintained or modified by its operators yet often vital to their existence. (Tenner)

The black box in The Lottery also fits the scientific description of a black box. The input is only blank, white papers and one white paper with a dot. In the black box, this white paper with the black dot is transformed into a death sentence. The formula applied to the white paper with the dot, transforming it into a death sentence, is a mixture of tradition and ideology. This also means that the black box is at the same time a symbol for tradition and ideology. The connection is so strong, that the term “black box” could be replaced either by tradition or ideology in the text passages describing the box.

“There was a story that the present box had been made with some pieces of the box that had preceded it, […]” (Jackson 588) could also be read as “There was a story that the present tradition (of the lottery) had been based on pieces of ancient (fertility) rituals that had preceded it. Like the new box is made of remnants of a proceeding, older box, only a few aspects of the preceding, ancient rituals, believes and ideological reasons for the lottery were incorporated into the new lottery ritual. The current version of the lottery ritual is only a part of the ancient version, like the box is only made of parts of the old box.

“Every year, after the lottery, Mr. Summers began talking again about a new box, but every year the subject was allowed to fade off without anything’s being done” (Jackson 588). This sentence could also be read as “Every year, after the lottery, Mr. Summers began talking again about a new (less deadly or violent) tradition based on a new ideology but every year the subject was allowed to fade off without anything’s being done” (Jackson 588). After the killing Mr. Summers seems to have at least for a few days something like a bad conscience. But this bad conscience seems to fade with time, in him and in the other villagers, and the topic of abandoning or altering the lottery is again and again dropped.

“The black box grew shabbier each year; by now it was no longer completely black but splintered badly along the side to show the original wood color, and in some places faded or stained.” (Jackson 588) This sentence is a symbolic description of the fading knowledge about the reasons for the lottery. The sentence could be reformulated as “The tradition grew more and more opaque each year; by now it was no longer completely accepted all the villagers and first voices became loud criticizing the ritual and the lottery began slowly to show its true gruesome killing mechanics, and in some places people started to abandon the tradition.”

Why though do the citizens of this village still obey to the rules of a ritual which roots and reasons are unknown to them although other villages have abandoned the ritual? This question might be answered by some famous psychological experiments and philosophy.

2.2.1 Mob behavior, obedience and diffusion of responsibility

In 1996 Gary Hamel and C.K. Prahalad published a business book called Competing for the Future. In this book the authors allegedly described the now famous 5 Monkeys Experiment for the first time. The modern day fable of the 5 Monkeys spread over the Internet and many years this experiment was seen as a parable to human behavior that never took place.

The parable as it is told across the Internet is a good one and it alone already explains mob behavior as it can be observed in daily life. Something Edgar Schein calls “unconscious, taken-for-granted beliefs, perceptions, thoughts and feelings. The ultimate source of values and action” (c.f. Anderson). “This is a classic example of Mob Mentality-bystanders and outsiders uninvolved with the fight – join in “just because”” (Anderson).

The Experiment according to Gary Hamel and C.K. Prahalad was carried out according to the following experimental setup:

Figure 1 Five monkeys, a ladder, a banana and a water spray (Skeptics Stack Exchange)

If one reads the original paper from 1967 that inspired the 5 monkeys and a ladder fable it is even more interesting, especially concerning The Lottery. The team of Gordon R. Stephenson used a not clearly defined “object” that was “manipulated” by the monkey, a cage and an air blast for punishment. The results though were different from the parable allegedly told by Gary Hamel and C.K. Prahalad.

In the critical test sequence, designed to test for transfer of a learned response, the learned response toward the reinforced object was transferred with lasting consequences from the demonstrator subject to the naïve partner in three cases; all of them involved males. In three other cases, all females, the information was not transferred, but instead, the avoidance response of the demonstrator was gradually extinguished as the non-conditioned naïve partner proceeded to manipulate the object. (Stephenson 284)

Yes, this mob behavior seems to exist in monkey societies, as told by the parable but only male monkeys seem to really enforce it. The female monkeys were able to analyze and to question the learned rules and ignore the “tradition” if it contradicted the facts at hand. That is more or less, what the reader can observe starting to happen in The Lottery. The patriarchate enforces this ritual without questioning it, as it has always been this way and it works. The only resistance comes from the women, as mentioned above in chapter 2.1.1. It seems this is an inherent trait in monkeys and in humans. Patriarchal systems seem to prefer to stick to unfounded rules while female monkeys and female humans, seem to question the status quo if it contradicts the observable facts. “Observational learning and admonition are distinguished as two types of information transfer between subjects which mediate the acquisition of culture in monkeys” (Stephenson 288) and it seems also in humans.

The Stephenson Experiment from 1967 explains mob behavior in patriarchal systems. Why many people obey arbitrary rules set or invented by leaders was explained a few years earlier in the famous and notorious first Milgram Experiment published in 1963 under the inconspicuous title Behavioral Study of Obedience (Milgram, “Behavioral Study of Obedience”). The paper describes “[…] a procedure for the study of destructive obedience […]. It consists of ordering a naïve S to administer increasingly more severe punishment to a victim in the context of a learning experiment” (Milgram, “Behavioral Study of Obedience”).

In this Experiment a “naïve subject […] adiminister(ed) electric shock(s) to a victim. A simulated shock generator is used, with 30 clearly marked voltage levels […]” (Milgram, “Behavioral Study of Obedience”). Although

Subjects have learned from childhood that it is a fundamental breach of moral conduct to hurt another person against his will. Yet 26 subjects abandon this tenet in following the instructions of an authority who has no special powers to enforce his commands. (Milgram, “Behavioral Study of Obedience”)

“14 Ss broke off the experiment at some point after the victim protested […]”(Milgram, “Behavioral Study of Obedience”). Unfortunately Milgram did only test male subjects. Would women have broken up the experiment more often or earlier, similar to the female monkeys in the Stephenson experiment? This would be valuable information that is unfortunately completely missing in the paper and also in the follow up paper from 1964: Group pressure and action against a person. In 1964 again only male subjects were tested. Milgram wanted to find out about the “relationship between a genuinely accepted belief and its transformation into behavior” (137). The setup was similar to the experiment conducted in 1963 this time though; the test subject had to perform the task of punishment by electric shock while “2 confederates […] call for increasingly more powerful shocks against a victim.”

There is little reason to assume a priori that observations made with regard to verbal conformity are automatically applicable to action. A person may pass lip service to the norms of a group and then be quite unwilling to carry out the kinds of behavior the group norms imply. Furthermore, an individual may accept an even promulgate a groups standard at the verbal level, and yet find himself unable to translate the belief into deeds. (Milgram, “Group Pressure and Action against a Person”137)

The results of the experiment showed that “the confederates substantially influenced the level of shock administered to the Learner” (139).

[…] (G)roup influence can shape behavior in a domain that might have been thought highly resistant to such effects. Subjects are induced by the group to inflict pain on another person at a level that goes well beyond levels chosen in the absence of social pressure. […] (A) substantial number of subjects submitted readily to pressure applied to them by the confederates (141f).

This alone though is still not enough to fully explain the villager’s behavior, especially the behavior of the dignitaries. Why do they organize the lottery in such an orderly way? Why don’t they feel responsible for organizing the killing?

There is still one further aspect that has to be taken into consideration. This aspect is called “diffusion of responsibility”. The philosopher Günther Anders wanted to understand how the Holocaust and the atomic bomb could have happened. According to him, one could say that the dignitaries see this lottery just another “job” that has to be done. Their act of counting the villagers and marking on paper with a dot is a neutral act. “Während Arbeit als solches unter allen Umständen als “moralisch” gilt, gelten in actu des Arbeitens Arbeitsziel und –Ergebnis […] grundsätzlich als „moralisch neutral“ […]“ (Anders 289). Additionally in this village, or in this culture that the village is only a part of, it is virtuous to actively take part in the lottery. „Heut ist es eben „moralisch“, hier mitzutun; und damals war es eben „moralisch“, dort mitzutun“ (Anders 289). This is further supported by historical facts. Only few of the NS culprits had to answer charges during the Frankfurt Process of 1963. None of the 22 accused pleaded guilty. It were the culprits the population solidarized with not the victims (Korte).

All findings of the above mentioned experiments form the 1960s can already be found in the short story The Lottery in 1948. Like in the Stephenson monkey experiment the women question the tradition of the lottery because they have heard that “some places have already quit lotteries” (Jackson 590). Mrs. Adams, a woman, is at least one person that seems not to take part in the actual stoning procedure. It is the men who, with the power of patriarchy, keep the tradition alive just so because those who abandon it are a “(P)ack of crazy fools. […] Next thing you know, they’ll be wanting to go back to living in caves, nobody work anymore, live that way for a while” (Jackson 590). Old Man Warner response is not a real argument at all but a classical killer argument, a “just so” and “it has always been that way” argument. “[…] (T)hinly veiled cruelty keeps the custom alive. Savagery fuels evil tradition, not vice versa” (Coulthard 226). The villagers enjoy this ritual as “(a)lthough the villagers had forgotten and lost the original black box, they still remembered to use stones” (Jackson 593) (Coulthard 227)

The obedience aspect comes in at the moment, when Mr. Summers calls to action.

“All ready? […] Now, I’ll read the names – heads of families first – and the men come up and take a paper out of the box. Keep the paper folded in your hand without looking at it until everyone has had a turn. Everything clear?” (Jackson 590)

Nobody is forced to take part in the lottery. The villager could just refuse or just not show up as a whole family. Like in the first Milgram Experiment, Mr. Summer can’t force them, the same way the experimentator in the Milgram Experiment had no way to force the test subjects to comply. But still they obey as he is one of the dignitaries of the village.

“Sie sind die Affen ihrer Gefängniswärter, beten die Symbole ihres Gefängnisses an und sind bereit, nicht etwa diese ihre Wärter zu überfallen, sondern den in Stücke zu reißen, der sie von ihnen befreien will” (c.f. Eisenberg). This citation by Max Horkheimer from his Book Dämmerung is completely in tune with the Stephenson experiment from 1967 and perfectly describes what is happening in this short story. They could resist, but anybody who would resist this lottery, would also be stoned to death, if not this year than the following one.

This village and its inhabitants mirror in their subjugation under the rule of the village dignitaries the ”socio-economic stratification that most people take for granted in a modern capitalist society” (Shields 415).

Would the villagers also comply if the master of the lottery ceremony was just a poor farmer or chosen every year by lot? Perhaps the group influence would still be enough to force the villagers to obey the rules of the lottery, like in the second Milgram Experiment, as there is a strong group influence present in this lottery ritual. Husbands force their wives like Mr. Hutchinson forces the slip of paper out of his wife’s hand, the old force the young to take their turn in the lottery and the very young ones just do not know what is really going on and do as they are told by their peers.

The diffusion of responsibility included in the makeup of the lottery ceremony makes sure that nobody is guilty. The dignitaries only do their job. It is no crime to fold white slips of paper or to mark a paper with a dot. The victim draws for himself or herself it is her or his (bad) luck or fault. And nobody can be sure that is was his or her stone that killed the chosen one. Nobody is guilty in the end but the victim who took the wrong lot. According to Amy Griffin “the base actions exhibited in groups […] do not take place on the individual level, for here such action would be deemed “murder”. On the group level people classify their heinous act simply as “ritual” (Griffin 45). In the end “(a) sense of community is won at a price, and communal guilt and fear are seen as more binding than communal love” (c.f. Wilson 147).

3 The effect of the writing style on the reader

Perhaps the answer as to why the villagers act this way is even simpler and can be summed up in Hanna Arendt’s famous citation from Eichman in Jerusalem “It was as though in those last minutes he was summing up the lesson that this long course in human wickedness had taught us-the lesson of the fearsome, word-and-thought-defying banality of evil” (253). Or, even shorter, with the words of the Roman author Titus Maccius Plautus: “homo homini lupus”.

This message about the “banality of evil” is also conveyed by the narrative style of the short story. The reliable, detached, heterodiegetic, 3rd person narrator with its external focalization invokes reminiscences of bureaucratic reports, like state reports about the goings on in the liberated Nazi concentration camps. This “feeling” of a bureaucratic report of a crime is further enhanced by the flatly drawn characters and the unrevealing dialogues: “Lots of conversations in this town, but no real voices. Platitudes, but no ideas; conformity trapped inside die illusion of freedom, the illusion of free speech” (Callaghan 96). Due to this style the readers are unable to identify or feel emotionally attached to the characters and the story becomes a modern-day parable tackling timeless issues with contemporary meaning (Wilson). The anonymity of village further emphasizes the universality of the event.

“The lottery taps directly into the observation that evil can be committed in a nonchalant, everyday way by people just like you and me” (Berkowitz). As the readers are unaware of the narrator, they become themselves one of the crowd of anonymous villagers, they become onlookers, bystanders and even more or less active participants of the stoning procedure (Shields 415). Additional to being the perpetrators the readers “are presented with a moral and ethical scene and sit as judge and jury” (Shields 415). A schizophrenic situation of double vision is the result.

All dies führt zwangsläufig zu einem Schock beim Leser, der die Trägheit in Individuum und Gesellschaft bewußt machen und einen Erkentnisprozeß einleiten soll. Er ist verbunden mit einem Appell gegen Brutalität und Erbarmungslosigkeit und gipfelt in der Mahnung das Leben zu achten. (Freese 108)

With this detached style Jackson succeeds to “create a spector of a holocaust in the United States” (Yarmove 245) that makes the reader “feel” or “understand” both sides of the Holocaust making it hard to really feel morally superiority to the Germans and rubbing in the message that “The Final Solution may have been unstoppable by American Jewry, but it should have been unbearable for them. And it wasn’t” (c.f. Novick 30). Not only the American Jewry and the Germans had been bystanders, the Americans had also been bystanders until the end and thus no right at all to feel morally superior in any way.

4 Conclusion

Shirley Jackson must have been a very keen observer of human behavior. Long before behavioral experiments in the 1960 proved her cynical observation of humanity she accurately described these group dynamic behavioral patterns in The Lottery. It is consequently no wonder that the readers of the first publication in The New Yorker were angered because they must have felt caught in the act. This also explains why this short story still today attracts and fascinates readers, as it describes daily human behavior as we know it from school, work, politics, family or neighborhood and makes it consequently a target for censors (Karolides 358). Perhaps censors don’t like that this story is “a useful means for enlightening students about the law. […] One of the story’s mayor ironies is that an activity leading to a triumph of antisocial forces over civilized restraint is carried out very meticulously according to “laws””. Laws do not secure safety they often threaten safety (Karolides 359). This is a dangerous message to convey in times of the US homeland security act, data mining though the security agencies all around the world or laws like the “ley mordaza” in Spain. In times where free media questioning the states actions are accused of “#Landesverrat” it might become even, or perhaps especially, nowadays increasingly dangerous to teach stories like The Lottery as “The Lottery encourages speculation on the most basic moral issues” (Karolides 361). Since the 1980s the story seems to have been unobtrusively removed from most anthologies. Ironically, if ever this story should be officially forbidden this will be due to exactly those dangerous human behavioral mechanisms described in it (Karolides 362).

“When you think of the long and gloomy history of man, you will find more hideous crimes have been committed in the name of obedience than have been committed in the name of rebellion” (c.f. Milgram)

Or like Senca said: Quædam iura non scripta, sed omnibus scriptis certiora sunt (Some laws are unwritten, but they are better established than all written ones).

5 Works cited

Anders, Günther. Die Antiquiertheit Des Menschen Band 1. C. H. Beck, 2002. Print.

Anderson, Carol. “The Monkey Experiment and Edgar Schein.” N.p., 2013. Web. 18 Aug. 2015.

Berkowitz, Roger. “The Banality of Evil and Shirley Jackson’s ‘The Lottery.’” Hannah Arendt Center for Politics and Humanities. N.p., 2014. Web. 20 Aug. 2015.

Blume, Thomas W. “Social Perspectives on Violence.” Michigan Family Review 02.1 (1996): n. pag. Web. 18 Aug. 2015.

Callaghan, Michael J. “Thomas Merton Goes to Class: Pedagogy on the Borders of the Short Story.” CEA Forum (2011): n. pag. Print.

Coulthard, A. R. “Jackson’s ‘The Lottery.’” Explicator 48.3 (1990): 226–228. Print.

Crane, Gregory R, ed. “Perseus Digital Library.” Tufts University. Tufts University, 2015. Web. 17 Aug. 2015.

Eisenberg, Götz. “Das Rätsel Der „freiwilligen Knechtschaft“.” NachDenkSeiten – Die kritische Website. N.p., 2014. Web. 17 Aug. 2015.

Florida Center for Instructional Technology. “Bystanders.” A Teacher’s Guide to the Holocaust. N.p., 2005. Web. 14 Aug. 2015.

---. “Holocaust Timeline: Aftermath.” A Teacher’s Guide to the Holocaust. N.p., 2005. Web. 14 Aug. 2015.

Freese, Peter [Hrsg.]. Die Amerikanische Short Story Der Gegenwart : Interpretationen. Berlin: Erich Schmidt Verlag, 1976. Print.

Gibson, James M. “An Old Testament Analogue for ‘The Lottery.’” Journal of Modern Literature (1984): n. pag. Print.

Griffin, Amy A. “Jackson’s ‘The Lottery.’” Explicator 58.1 (1999): 44–46. Print.

Jackson, Shirley. “The Lottery.” An Introduction to Short Fiction. Ed. Ann Charters. 7th ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2007. 586–593. Print.

Karolides, Nicholas J. [Hrsg.]. Censored Books : Critical Viewpoints. Metuchen, NJ [u.a.]: Scarecrow, 1993. Print.

Korte, Jan. “Keiner Der Angeklagten Bekannte Seine Schuld.” Fraktion DIE LINKE. im Bundestag. N.p., 2015. Web. 19 Aug. 2015.

Milgram, Stanley. “Behavioral Study of Obedience.” Journal of abnormal psychology 67 (1963): 371–8. Web. 17 Aug. 2015.

---. “Group Pressure and Action against a Person.” Journal of abnormal psychology 69 (1964): 137–43. Web. 19 Aug. 2015.

Novick, Peter. The Holocaust and Collective Memory : The American Experience. London: Bloomsbury, 2000. Print.

Oehlschlaeger, Fritz. “The Stoning of Mistress Hutchinson: Meaning and Context in ‘The Lottery.’” Essays in Literature 15.2 (1988): 259–265. Print.

“Old History Is New Again: Ancient Carthaginians Did Sacrifice Their Children.” ION Publications LLC. N.p., 2014. Web. 17 Aug. 2015.

Shields, Patrick J. “Arbitrary Condemnation and Sanctioned Violence in Shirley Jackson’s ‘The Lottery.’” Contemporary Justice Review 7.4 (2004): 411–419. Print.

Siculus, Diodorus. “Lacus Curtius Book XX.” Loeb Classical Library edition. University of Chicago, 1954. Web. 17 Aug. 2015.

Skeptics Stack Exchange. “Psychology - Was the Experiment with Five Monkeys, a Ladder, a Banana and a Water Spray Conducted?” N.p., 2013. Web. 18 Aug. 2015.

Stephenson, G. R. “Cultural Acquisition of a Specific Learned Response Among Rhesus Monkeys.” Neue Ergebnisse Der Primatologie : 1. Congress of the International Primatological Society, Frankfurt a.M., 26. - 30. Juli 1966 = Progress in Primatology. Ed. H. J. Starek, D., Schneider, R., and Kuhn. Stuttgart: Fischer, 1967. 279–288. Web. 6 Aug. 2015.

Strabo. “The Geography of Strabo Vol. I., Translated by H. C. Hamilton.” The Project Gutenberg. N.p., 2014. Web. 17 Aug. 2015.

Tenner, Edward. “If Technology’s Beyond Us, We Can Pretend It's Not There.” The Washington Post. N.p., 2003. Web. 18 Aug. 2015.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “The United States and the Holocaust.” Holocaust Encyclopedia. N.p., n.d. Web. 14 Aug. 2015.

Williams, Richard H. “A Critique of the Sampling Plan Used in Shirley Jackson’s ‘The Lottery.’” Journal of Modern Literature 7 (1979): 543–44. Print.

Wilson, Kathleen, ed. “Gale Virtual Reference Library - Document - The Lottery.” Short Stories for Students 1. Gale, 1997. Web. 19 Aug. 2015.

Yarmove, Jay A. “Jackson’s ‘The Lottery.’” Explicator 52.4 (1994): 242–45. Print.